Portuguese and Spanish navigators sailed the Pacific Ocean in the 1500s, but there is no firm evidence that Europeans reached New Zealand before 1642.

In that year the Dutch explorer Abel Tasman sailed in search of the vast continent which many Europeans thought might exist in the South Pacific. Dutch merchants hoped this land would offer new opportunities for trade. Tasman sighted New Zealand on 13 December 1642, but after a bloody encounter with Māori in what he called ‘Murderers’ Bay’ (now Golden Bay/Mohua) on the 19th, he left without going ashore. Tasman then sailed up the west coast of the North Island but did not establish how far east land extended.

European exploration before 1769

John Byron’s voyage of 1764–66 is generally considered the beginning of serious English interest in the Pacific, which was encouraged by imperial rivalries with Spain, the Netherlands and France. In 1767 Samuel Wallis became the first European to visit Tahiti.

A new expedition: Cook’s First Voyage

By the time Wallis returned to England in May 1768, another expedition to the Pacific was already being organised. The Royal Society had proposed to the British Admiralty that the transit of Venus (the passage of the planet Venus across the face of the sun) be observed in the South Pacific. This observation, combined with others elsewhere, would make it possible to accurately calculate the distance from the Earth to both Venus and the sun. When Wallis returned with news of Tahiti, the expedition was instructed to go there to make the observations.

Video courtesy of Island Productions Aotearoa Ltd.

Dame Anne Salmond explains the enlightenment and forces that drove Europeans to explore the Pacific.

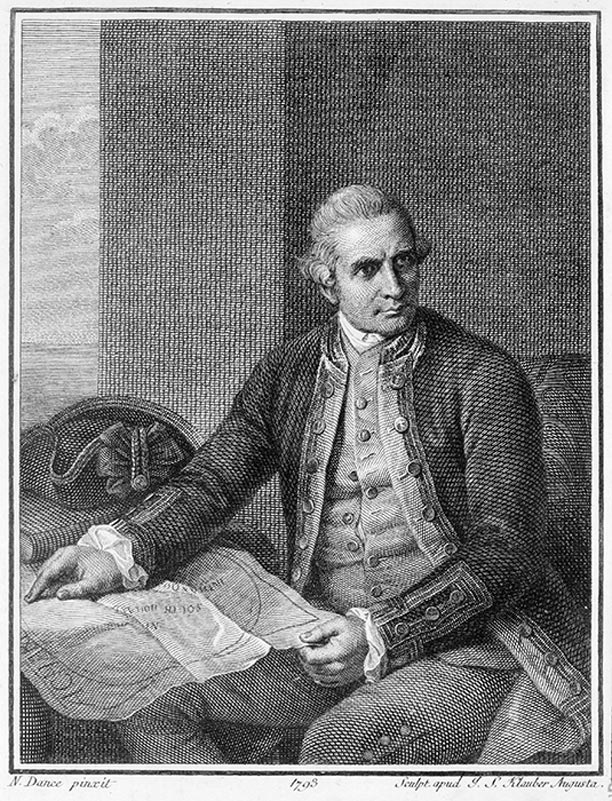

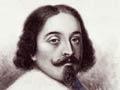

Lieutenant James Cook was appointed to command the expedition. Cook was approaching 40 and had 10 years’ experience in the Royal Navy, mostly in North American waters. Previous to the navy, Cook had worked in the coal trade, which turned out to be an advantage: the ship for the expedition was a former coal ship, a relatively small vessel of 368 tons, just 32 m long and 7.6 m broad.

Alexander Turnbull Library, Ref: A-451-009

Portrait of Lieutenant James Cook by Nathaniel Dance Holland.

The ship, renamed Endeavour, departed from Plymouth on 26 August 1768 with 94 men aboard. After entering the Pacific around Cape Horn, it arrived in Tahiti on 13 April 1769 and spent almost four months there.

One of Cook’s key companions was the gentleman naturalist Joseph Banks. Wealthy enough to indulge his interests, Banks paid for another botanist, the Swede Dr Daniel Solander, and three draughtsmen (artists) to join the expedition.

Because of its scientific emphasis, Cook’s voyage has often been viewed more favourably than Tasman’s. However, the English, like the Dutch, also wished to expand trade and empire – the British Empire had political, strategic and economic expansion in its sights. Cook included in his reports information about the resources of the lands he visited, and the suitability of those lands for settlement by Britain.

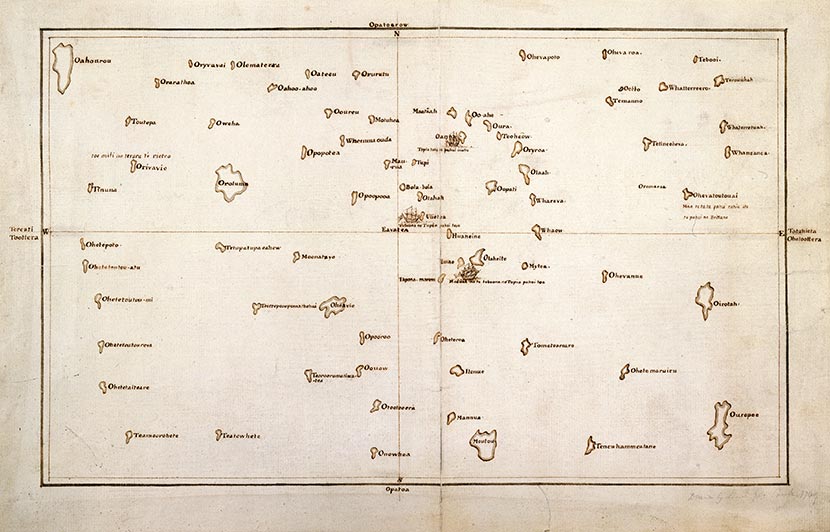

The third key figure aboard the Endeavour was Tupaia, a Tahitian arioi (high priest) who came on board at Tahiti. Until recent decades Tupaia’s crucial contribution has been largely invisible in accounts of Cook’s voyage. Tupaia was an expert navigator and helped Cook draw a chart showing the locations of more than 70 islands in relation to Tahiti.

British Library Reference: ADD MS 21593c.

Tupaia’s chart, 1769. Tupaia drew this iconic map of the Pacific during the journey with Cook from his homeland in Tahiti, demonstrating the vast knowledge of the South Pacific held by Polynesian voyagers. He dictated the names of 74 islands to be added to the chart.

Once the planetary observations had been made, Cook’s expedition was to locate Tasman’s outline of New Zealand and establish how far it extended to the east. The Endeavour sailed south into uncharted waters and then west. On 6 October 1769, the surgeon’s boy sighted the high hills of Aotearoa.

Video courtesy of Island Productions Aotearoa Ltd.

As the Endeavour travelled down from Tahiti to New Zealand, in August to October 1769, Cook and his crew battled rough seas, and had to cope with poor food and water. Also on board was Tupaia, the Tahitian arioi (high priest), whose experience of a voyaging life was very different. This video gives a taste of what it was like during this part of the journey.

According to some accounts, astonished Māori who saw the strange vessel from shore thought it was a floating island or the legendary bird Ruakapanga from Hawaiki. The people of Tūranganui-a-Kiwa were the first to meet Cook when he anchored. Conflict arose when the crew went ashore to seek water and supplies, and killed or wounded several Māori. (See also: Early Encounters.)

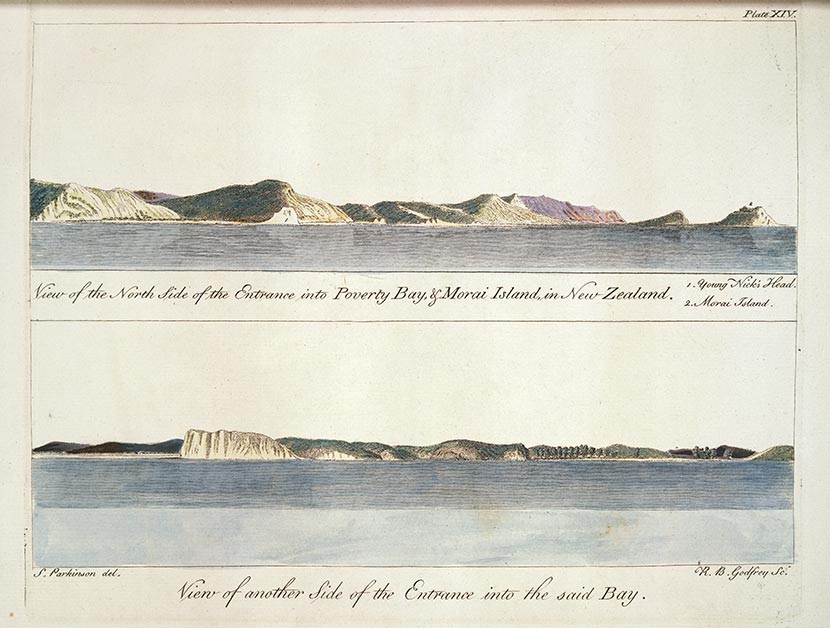

Alexander Turnbull Library Ref: PUBL-0037-14.

These engravings show the first part of Aotearoa seen by Cook and the crew of the Endeavour in October 1769 – Tūranganui-a-Kiwa, which Cook named Poverty Bay, including the headlands to the east of Gisborne city and Te Kurī-a-Pāoa, which Cook named Young Nicks Head after the ship's surgeon’s boy who was the first to see land. They are based on drawings by Sydney Parkinson, the artist on Cook’s first voyage to New Zealand.

The Endeavour then sailed south, before returning to the north, travelling up around Cape Reinga and down the North Island’s west coast to Queen Charlotte Sound/Tōtaranui. Longer stops occurred at Uawa (Tolaga Bay), Te Whanganui-o-Hei (Mercury Bay) and Pēwhairangi (the Bay of Islands).

Sydney Parkinson, Alexander Turnbull Library Ref: PUBL-0037-24.

This engraving shows a fortified pā on top of an arched rock at Mercury Bay, on the Coromandel’s east coast, seen by Cook in 1769. The arch has since collapsed.

At Queen Charlotte Sound/Tōtaranui, Cook anchored at Meretoto/Ship Cove, a haven he returned to on each subsequent voyage. From a high point on Arapawa Island he first saw the narrow strait that now bears his name. Sailing through this strait, he sailed up the east coast of the North Island until he confirmed it was indeed an island, then down the east coast of the South Island and round the southern tip of Stewart Island/Rakiura.

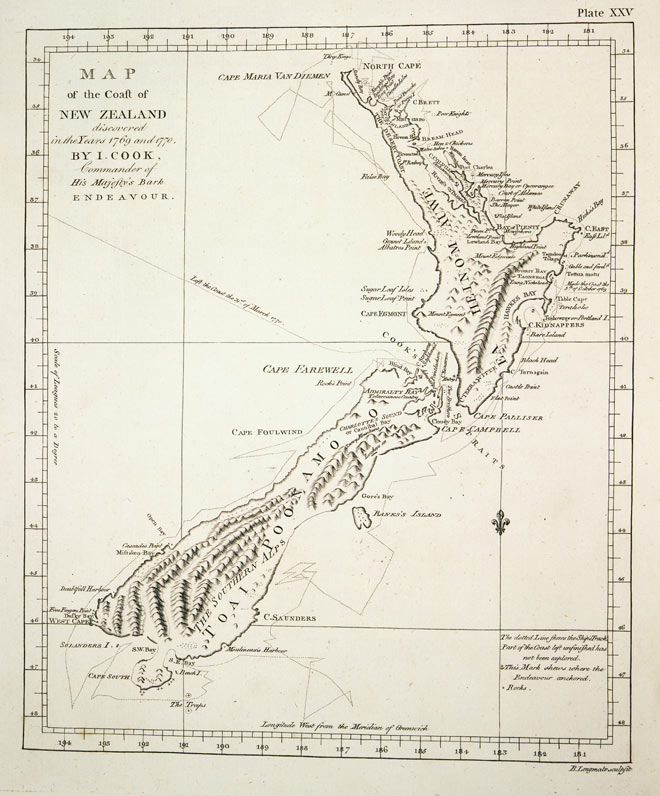

Alexander Turnbull Library Ref: B--098-015.

Cook stayed at Meretoto/Ship Cove in Queen Charlotte Sound/Tōtaranui at the top of the South Island on each of his three journeys to New Zealand. John Webber, the official artist on Cook’s third voyage, painted Māori fishing there.

After restocking water and wood at Rangitoto ki te Tonga/D'Urville Island, Cook sailed west to chart the east coast of ‘New Holland’ (Australia) and called at the Dutch colony of Batavia (now Jakarta), where Tupaia died of illness. Cook arrived back in England, having circumnavigated the globe, on 13 July 1771.

Alexander Turnbull Library. Ref: PUBL-0037-25.

Drawn by James Cook in 1770, after his first journey, this chart of New Zealand was remarkably accurate and detailed. His precision and scientific approach set a new standard for the mapping work of the British Admiralty.

Cook’s second and third voyages

Cook’s first voyage had confirmed to Europeans that New Zealand was not a vast southern land. A French expedition under Jean François Marie de Surville had also visited the northern North Island at the same time. Yet there still remained unexplored ocean to the east of New Zealand and further south.

On his second voyage (1772–75) Cook used New Zealand as a base for probes south and east which finally proved there was no such continent. The expedition had two ships: HMS Resolution, commanded by Cook, and HMS Adventure, commanded by Tobias Furneaux. Both ships sailed from England on 13 July 1772 and spent time in New Zealand waters between excursions into the unexplored parts of Antarctica and the Pacific.

State Library of New South Wales, Mitchell Library: PXD 11 f.32a

William Hodges, the artist on Cook’s second voyage, painted this view of the entrance to Dusky Sound in 1773.

On his third voyage (1776–79) Cook again commanded the Resolution, with Charles Clerke in command of the Discovery. Cook paid a last visit to New Zealand, staying from 12 to 25 February 1777 at ‘our old station’, Ship Cove in Queen Charlotte Sound, before sailing into the north Pacific and through Bering Strait to the north coast of Siberia. He was killed in an avoidable incident at Kealakekua Bay, Hawaii, on 14 February 1779.

New Zealand’s people, flora and fauna

Cook’s three voyages had touched all three corners of the Polynesian triangle – New Zealand, Hawaii and Rapa Nui (Easter Island) – and he and his associates recognised that ‘the same nation’ was spread over a vast extent of ocean. The scientist Johann Reinhold Forster, who travelled on the second voyage, identified what became known as the Austronesian language group.

Cook’s first voyage provided Europe with its first knowledge of the Māori people. The observations of Cook, Banks, Tupaia and others on the Endeavour are still valuable sources of information about Māori life at the time of the first encounters.

Having spent a total of 328 days on the coast, Cook and those with him left a vivid and comprehensive visual and written record of the country’s natural history. Few lands newly discovered by Europeans were so comprehensively documented. Banks’ and Solander’s collections of plants and their descriptions laid the foundations for modern New Zealand botany.

Exploration by other nations

At the same time as Cook was in New Zealand, and soon after, explorers from a number of other nations visited. As Cook rounded the top of the North Island in December 1769, the French explorer Jean François Marie de Surville was as little as 40 km to the south-west, just missing what would have been a historic meeting. In mid-December de Surville reached the east coast of the Far North, spending two weeks in Doubtless Bay.

On the heels of de Surville, in 1772 Marc Joseph Marion du Fresne spent more than two months in the Bay of Islands while undertaking extensive repairs. From the 1770s, New Zealand was used as a base for explorers seeking more challenging destinations. On his way to survey the north-west coast of North America, British naval officer George Vancouver spent three weeks in Dusky Sound in November 1791. In February 1793 the Italian explorer Alessandro Malaspina also called in to Dusky Sound on his way to Australia as the leader of a Spanish scientific expedition. A quarter of a century later, the German Fabian von Bellingshausen was sent to continue the work of Cook's later voyages by exploring the southern polar regions. His Russian expedition visited Queen Charlotte Sound for a week, using it as a base as Cook had. In 1824 the French explorer Louis Isidore Duperrey had a two-week stopover in the Bay of Islands before continuing on his circumnavigation of the world.

Duperrey's second-in-command in 1824 was Jules Sébastien César Dumont d'Urville. The expedition that Dumont d'Urville led in 1826 is considered to be the last important voyage in the story of the European discovery of New Zealand. D'Urville intended to complete Cook's chart of New Zealand; he explored Tasman and Admiralty Bays, and much of the east coast of the North Island.

For more information about these explorers, see the Te Ara entries on the French explorers and explorers from other nations.

Find more about European exploration on Te Ara

Objects that tell stories

Abel Tasman's Staten Landt

Tupaia’s chart

Cook’s Map of New Zealand

Chronometer

Drawing of a kauri tree

De Surville’s anchor

Native plants

Joseph Banks’s journal

Impressions of ‘Dusky Bay'

Biographies on the DNZB

Further Information

European discovery of New Zealand on Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

Abel Tasman 1642 – a site devoted to the 370th anniversary of Tasman's visit to New Zealand.

Captain Cook Society – a useful starting point for further research into Cook's life and work.

The Endeavour replica – images from the Australian National Maritime Museum.

James Cook Birthplace Museum – covers almost every conceivable aspect of Cook's life and work.

New Zealand place names given during Cook’s voyages – explore the stories of 30 of the place names associated with Cook and the Endeavour on Land Information New Zealand’s website.

Community contributions