Most 'Pākehā-Māori' were traders, whalers, sealers, runaway seamen, or escaped convicts from Australia. They settled in Māori communities, adopted a Māori lifestyle, and were treated by Māori as both Māori and as useful go-betweens with the Pākehā world. While some Europeans were viewed as slaves or kept as curiosities, others were given chiefly status and some received the honour of the moko (facial tattoo). While each Pākehā-Māori story is unique, together they illustrate the political, economic and social impact these people had in early 19th century Aotearoa New Zealand.

Barnet Burns

In the early 1830s, English sailor and trader Barnet Burns lived on the Māhia Peninsula and then at Tūranganui-a-Kiwa (Poverty Bay) and Ūawa (Tolaga Bay). At Māhia he was protected by a chief known as Te Aria, and married his daughter, Amotawa. Burns learnt to speak Māori, became a flax trader and fought alongside Te Aria's people. His negotiations between his Māori hosts and his British compatriots made him a significant cultural go-between in these early days of European settlement. Amotawa and Burns had three children together – Tauhinu, Mokoraurangi and Hori Waiti – before Burns returned to England. With his face tattooed he worked as a showman, exhibiting himself in a costume supposedly replicating that of a Māori chief.

Video courtesy of Rhonda Kite for KIWA Productions Ltd.

This video tells the story of Barnet Burns’ life in Aotearoa New Zealand, his return to England and his family legacy.

Dicky Barrett and Jacky Love

Traders and whalers Richard (Dicky) Barrett and Jacky Love formed an economic relationship with Te Āti Awa at Ngāmotu (now New Plymouth) in 1828. Both men were given Māori names: Barrett’s name was transliterated as Tiki Parete, while Love became known as Hakirau.

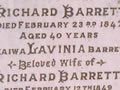

Acceptance into Te Āti Awa was sealed through marriage. Barrett’s wife, Wakaiwa (or Rawinia) was the daughter of Eruera Te Puke ki Mahurangi, a leading Ngāti Te Whiti chief, and she was related to many other important Te Āti Awa chiefs, including Te Wharepōuri and Te Puni. The couple's children wore European clothes, had Māori as well as English names, and spoke both languages.

In 1832, Barrett, Love and a number of other Europeans helped Te Āti Awa repulse a Waikato attack on Ōtaka pa, Ngāmotu. Te Āti Awa held out despite being outnumbered and running short of water and food. Love had been the first to see the invading waka, while Barrett later led a feint that exposed Waikato to fire from salvaged ships’ cannon. His mana boosted, Barrett joined Te Āti Awa on an overland hīkoi to Port Nicholson (Wellington), where they resettled and planted crops. Barrett became a leading figure in Port Nicholson and acted as interpreter for the New Zealand Company in its dubious land purchases in the Cook Strait region.

Video courtesy of Rhonda Kite for KIWA Productions Ltd.

In this video the Love family tell the story of their Pākehā tīpuna Jacky Love and Dicky Barrett.

Manuel José

For Māori, marriage was one way to attract a Pākehā and keep him in the community. Any resulting children stayed within the tribe. As hapū and iwi sought to gain an advantage over their rivals, acquiring a European trader became a matter of both mana and economics. Most trading, timber and whaling stations – and individual traders – soon became linked to Māori through marriage. The Spanish whaler, Manuel José lived in the Waiapu district on the East Coast of the North Island from the late 1830s, working as a trader. He married five chiefly Ngāti Porou women, having five children with one of them and one with each of the others. He now has several thousand descendants in the region.

Video courtesy of Rhonda Kite for KIWA Productions Ltd.

Listen to Manuel José’s story and hear from some of these descendants.

Jackie Marmon

Some Pākehā-Māori had more than one stay in Aotearoa New Zealand. John (Jacky) Marmon, for example, was a mariner who travelled throughout the ‘south seas’ and regularly came to New Zealand. He was about 17 when he first lived with Maori and about 24 when he settled with Kawhitiwai in the Hokianga.

He was at first adopted for novelty value but once he mastered te reo Māori he gained mana and asserted his authority. He proved his economic value as a trader and when he played a significant role in helping Māori acquire guns. The large, redheaded Irishman was feared and revered for his fighting abilities. He refused to adjust to colonial New Zealand life, preferring to live amongst Māori. Like other Pākehā-Māori Marmon had several wives and many descendants remain to tell his story.

Video courtesy of Rhonda Kite for KIWA Productions Ltd.

Listen to Manuel José’s story.

Phillip Tapsell

Norwegian Hans Felk, who took on the name Phillip Tapsell (‘topsail’), had served on merchant ships and claimed to have been a prisoner of war in Sweden and a pirate. It was his work on whaling ships in the 1820s that brought him to Aotearoa New Zealand.

In 1830 Tapsell settled in Maketu in Bay of Plenty at the invitation of a Te Arawa chief. He married Hine A Turama, a Ngāti Whakaue woman of high rank and they had six children together.

In 1837, Phillip Tapsell set up a trading station at Whakatane which employed several Pākehā-Māori as agents for the sale of flax and muskets. He was known to be a fair trader and evenhanded in his distribution of muskets amongst different hapū and iwi. Over the years, the family came to be highly regarded for the strong economic base they established for several Bay of Plenty iwi.

Phillip Tapsell lived among Māori for 50 years. His lasting legacy now includes more than 3500 descendants.

Video courtesy of Rhonda Kite for KIWA Productions Ltd.

Listen to Phillip Tapsell’s story.

Frederick Maning

Anglo-Irish trader Frederick Maning described himself as a Pākehā-Māori but from 1840 lived in a European-style house at Ōnoke in the Hokianga with his Ngāpuhi wife Moengaroa, the sister of the young chief Hauraki. The couple had four children and Maning’s letters after Moengaroa’s death in 1847 express his intense grief.

Maning learnt the Māori way of life and observed tikanga Māori but remained European in his outlook. He saw himself as being caught between two worlds, and at first opposed the introduction of British law.

Unlike many Pākehā-Māori, Maning was literate. He wrote a memoir, Old New Zealand: a tale of the good old times by a Pakeha Maori. In later life he became a land court judge.

His deep connection with Māori and Aotearoa New Zealand continued throughout his life. He returned to England at the age of 72 to seek treatment for cancer, but died soon after his arrival. At his request, his body was returned to Auckland for burial.

Video courtesy of Rhonda Kite for KIWA Productions Ltd.

In this video you can hear about Frederick Maning from his descendants.

Credit

The videos from this page are from material preserved and made available by Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision, Reference: F61746 - Pākeha-Māori (2004).

Video courtesy of Rhonda Kite for KIWA Productions Ltd.