Julius Vogel wasn't the first colonial politician to promise to fund public works and immigration with borrowed money. But the early 1870s offered better prospects for success. War in the North Island was all but over. The main British railway network was largely complete, so English contracting firms like John Brogden and Sons were looking for new opportunities overseas. An outbreak of rural unrest in Britain also encouraged farm labourers to undertake the long and difficult sea voyage to New Zealand.

Along the lines

Road and telegraph networks were extended at the same time as railways were built. The former often provided access to rail construction sites or linked railheads, and the latter frequently followed rail lines. By 1876 New Zealand had an undersea telegraph link to Australia, which reduced communication with Europe to a matter of hours.

The colonial government contracted Brogdens to build railways and recruit migrant workers. In 1872–3 they brought 2200 English immigrants here, including 1300 working-age men (mostly agricultural labourers) contracted to two years’ work on railway construction. Brodgens’ ‘navvies’ (this common name for public works labourers derived from the ‘navigators’ who had dug Britain’s 18th-century canals) set to work on contracts at or near Auckland, Napier, Wellington, Picton, Oamaru and Invercargill. They worked by hand using simple tools – picks and shovels, horses and carts, and dynamite – and endured primitive living conditions in isolated camps.

Problems with the plan

Rail construction forged ahead, despite occasional delays, labour shortages and industrial disputes over wages and conditions (not least the local custom of an eight-hour working day). By the mid-1870s the government was offering assisted passages from Britain without any work obligations. Many disgruntled navvies broke their contracts and drifted into farming, urban jobs or gold-prospecting. British recruitment was soon abandoned; from now on navvies would be recruited locally.

By 1873, when Vogel became premier, other tensions were emerging. Members of Parliament and local Railway Leagues were lobbying for rail lines through their electorates and towns. More borrowing was needed, an estimated £1.5 million (equivalent to $200 million in 2018) for railways alone in 1873. To guarantee further loans and help pay for the scheme, Vogel proposed to reserve 6 million acres (2.4 million ha) of ‘wasteland’ along rail routes as a Crown endowment. But South Island provincialist MPs feared a central government land grab and defeated the proposal in Parliament. Vogel and his allies plotted their revenge.

Although provincial feelings remained strong, politicians increasingly realised that only central government could pay for and carry out such an ambitious nation-building programme. The abolition of the provinces was carried in Parliament in October 1875 and came into effect a year later. By that time the Vogel ministry had lost power, but subsequent governments continued to pour money into public works. Along with rail development itself, the abolition of the provinces was a key element in the emergence of a strong central government in New Zealand.

A network emerges

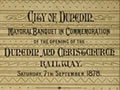

Vogel’s rail plan initially made its greatest strides in the South Island. A Christchurch–Dunedin railway was completed in 1878, cutting travel time between the South Island’s largest cities to around 11 hours. The following year New Zealand’s first ‘main trunk’ line linked Christchurch with Invercargill, while a series of branch lines snaked inland from the coast.

Auckland’s first railway, between the city and Onehunga, was built by Brogdens and opened in 1873. More significantly, within 18 months the South Auckland line – following in the footsteps of General Cameron’s Imperial troops a decade before – had reached the Waikato basin, opening up a million acres (405,000 ha) of recently confiscated Māori land to Pākehā settlement and exploitation. By 1880 rails reached Te Awamutu, on the border of Te Rohe Pōtae (the King Country), the Māori heartland into which the Kīngitanga tribes had withdrawn after the Waikato War.

Wellington’s first railway, opened in 1874, ran between Thorndon and Lower Hutt. By 1878, following the completion of the ambitious Remutaka incline railway, the capital was linked to the Wairarapa plains. Elsewhere in the North Island, railways were built in the Bay of Islands, north-west Auckland, Taranaki, Hawke’s Bay and Manawatū.

By 1880 the government-owned New Zealand Railways was operating almost 2000 km of working railway, three-quarters of it in the South Island. In the centre of the North Island, rugged landscapes and resolute Māori landowners had slowed rail’s progress. Following lengthy negotiations with Ngāti Maniapoto, work on the central section of a North Island main trunk railway began in 1885 (by which time Vogel was Treasurer again). The eventual completion of the main trunk in 1908, nine years after Vogel’s death, represented the realisation of his 1870 vision.