More than 3000 ‘animals’ - horses and mules - went from Egypt to France with the New Zealand Division in April 1916. Most of these horses had probably come from New Zealand originally.

The majority of the riding horses transported from New Zealand were assigned to the Auckland, Wellington and Canterbury mounted rifles regiments, which remained in the Middle East as part of the new Anzac Mounted Division. But riding horses were also assigned in smaller numbers to the units which went to France. A significant number were assigned to the Otago Mounted Rifles Regiment, which was reduced to a squadron in March 1916 and reorganised as the Divisional Mounted Troops. In The troopers’ tale, historian Christopher Pugsley noted that the OMR ‘brought over from Egypt a large number of its horses, over and above its requirements in France’.

Most of New Zealand’s draught, heavy draught and packhorses were assigned to units that went to France, especially the infantry and artillery.

Finnigan: Gallipoli veteran

Finnigan, a Royal New Zealand Artillery horse from New Zealand, served at Gallipoli and on the Western Front. He is said to have been wounded twice at Anzac Cove. When the artillery moved to France he was wounded in action on another two occasions. Finnigan died during the Battle of the Somme after stepping on an unexploded bomb on the road near Flers.

Before joining the rest of the New Zealand Division in its billeting area the artillery, the transport sections of other units, and their horses went via imperial base and remount depots. At remount depots they exchanged unfit horses for enough fit ones to bring the units up to establishment. They replenished their equipment at the base depots, guns and wheeled vehicles having been left behind in Egypt (with the exception of the artillery’s telephone carts). While the artillery and their horses went to depots at the port of Le Havre, most transport sections and their horses went to Abbeville.

It is unclear how many New Zealand horses were exchanged at this point or in the years that followed. References to the high quality of the New Zealand horses and the affection the men had for them suggest that the New Zealanders did their best to hold on to them.

Horses proved more useful to New Zealand forces on the Western Front than they had been at Gallipoli. Riding, draught, heavy draught and packhorses were used to varying extents for troop work, artillery and transport purposes.

Riding horses were used by troops and officers across the New Zealand Division on the Western Front. But the greatest number were utilised by the Otago Mounted Rifles. In The troopers’ tale, Christopher Pugsley explains that mounted troops and cavalry played a ‘very limited’ role on the Western Front because of the trench warfare that followed the opening battles of 1914. As at Gallipoli, the mounted men of the OMR sent to the Western Front were called upon to perform dismounted work – everything from ‘repairing, draining and digging trenches’ to ‘salvaging artillery ammunition and the useful detritus of war’. But unlike at Gallipoli the unit retained and maintained its horses, and was sometimes called upon to perform mounted work. This included responsibilities such as ‘escort duty, traffic control and small detachments for miscellaneous mundane tasks’, but also a forward reconnaissance role, notably at the Battle of Messines in June 1917.

Draught, heavy draught and packhorses were generally able to carry out the tasks they had been sent overseas for, such as drawing the artillery’s guns, howitzers and ammunition waggons. But conditions on the ground – such as deep mud and shellholes – sometimes hampered their efforts. Progress could be slow, even when larger than usual teams of horses were employed. During the Battle of the Somme in September 1916, the 10th Battery found the road to its new position in such an ‘indescribable state’ that even when it employed ‘twenty horses … to each gun’ instead of the standard six-horse team, it took many hours to reach their destination.

As at Gallipoli, the artillery was at times forced by the conditions to manhandle its guns and ammunition into place. On other occasions horses were superseded by mechanical transport. During the Battle of Messines in June 1917, light rail was used to transport large amounts of ammunition to forward positions.

Conditions on the Western Front were often physically trying for the horses. Sometimes food, water or suitable shelter was in short supply. They suffered particularly in winter because of the dampness and mud. The winter of 1916-17 was said by locals to have been the worst for 40 years. Horses soon lost condition and became more susceptible to disease.

Many horses were injured, wounded or killed in action. ‘Very frequent and serious injuries’ were caused when nails penetrated their hoofs. Nails littered roads in the war zone, particularly near dumps and ruined houses. Actions could be costly: the Otago Mounted Rifles lost eight horses and had 32 wounded during the Battle of Messines. Losses also occurred as units advanced to new positions, and occasionally as a result of shellfire or aerial bombing in rear areas where horses were tethered or stabled together.

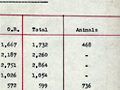

Given such losses, and the exchange and replacement of horses – for example, with horses and mules from North America – it is unclear how many New Zealand horses were still serving with the New Zealand Division at the end of the war. The New Zealand Division had just under 4500 ‘animals’ on 31 December 1918.