Using this page

This page looks at the use of place names to teach history. It outlines teaching considerations, the history behind the names Aotearoa and New Zealand, and offers perspectives around ideas connected to whakapapa, identity, and the current debate about what to call this country. These perspectives are supported with activities to use and/or adapt for your class.

Curriculum

This page supports an integrated approach to teaching the big ideas of Aotearoa New Zealand histories. It would be particularly useful for students exploring the context of Tūrangawaewae me te kaitiakitanga | Place and environment

Key concepts

This page explores key historical concepts, including:

- place/belonging

- identity

- whakapapa

- change and continuity

- values and perspectives.

Overview

Place names are a great way to learn about history. Names are symbolic – they carry whakapapa and stories. Names can shed light on great feats, remember horrific events or simply convey mundane acts. Names help us to remember and to connect with culture and heritage.

Māori place names

Ngā tohu pūmahara: the survey pegs of the past (PDF, 3.7MB) is a great rauemi (resource) to learn about Māori place names. It explains how they often describe features in the land and identify resources, acting as records of past actions, or ‘survey pegs of memory’. Ngā tohu pūmahara points out potential fishhooks and difficulties when trying to decipher Māori place names, providing context that teachers need to be wary about.The act of naming land is an assertion of presence, a signifier of occupation, a statement of power. Older Māori names were often supplanted as iwi encountered, occupied, or conquered new territory. And then, through colonisation, English names were imposed over Māori names. These new names were tied to the cultivation of identity in a new land – many were directly imported from Britain. Giselle Byrnes writes, ‘The map of New Zealand reads like an inventory of British imperial history: Wellington, Nelson, and Hastings.’ Unlike Māori place names, English names often have no connection to each other but stand on their own, like individual memories.

Map: Naming the country and the main islands

Manatū Taonga Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Naming the country and main islands map (accessible version).

Place names

Names are revealing – I remember the shocked surprise of students from a girls’ school when they learned that their school ‘house names’ were all those of dead white men. There is power in naming.

Resource: start local

Use the following questions as prompts:

- What is the history behind your school’s name?

- Does your school have a pepeha – what are the stories associated with maunga, awa, moana?

- What is the history embedded in names around your school and community? Use these names to springboard into concepts like power, identity, and values.

- How relevant and appropriate are the names, and what stories do they tell?

We are living in a time when colonial names are being questioned and Māori names are reasserting themselves in the landscape. This trend is connected to a broader movement of decolonisation and te reo revitalisation, and a growing awareness of how power has shaped history. This history is alive – it is possible to feel the past and the present interacting with one another.

What to do with markers of our colonial past? – Te Akomanga

Tangata whenua place names – Toitū Te Whenua Land Information New Zealand

Before we summarise the history of the names Aotearoa and New Zealand, it is worth remembering that no single Act of Parliament or authority makes ‘New Zealand’ an official name. Rather, it is the consistent use of ‘New Zealand’ in constitutional documents such as te Tiriti o Waitangi and the New Zealand Constitution Act 1852 that has created its official status.

Te reo anthem

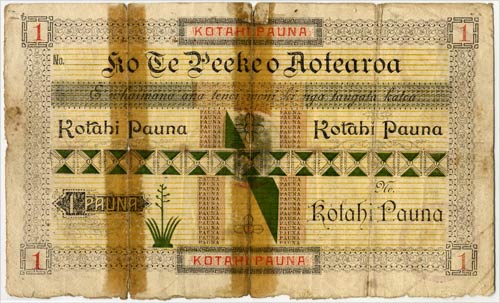

The singing of the national anthem in te reo Māori (as ‘Aotearoa’, translated in 1878), has never been formally authorised but has become commonplace. Watch as Hinewehi Mohi sings it for the first time before an All Blacks rugby game.Today, government departments often use ‘Aotearoa’, which also appears on the national currency and on drivers’ licences. The histories curriculum uses the term Aotearoa New Zealand.

The report into the Wai 262 claim is entitled Ko Aotearoa tēnei (This is Aotearoa). And one of the commonest expressions of personal and national identity is the ‘Uruwhenua Aotearoa New Zealand’ passport.

Ko Aotearoa Tēnei: Report on the Wai 262 Claim Released – Waitangi Tribunal

Naming Aotearoa and New Zealand

Aotearoa is a name that begins with the Polynesian migration to these islands; it is a name captured in Māori whakapapa and pūrakau, and more recently a name attached to emerging cultural and political identity. The origins of the kupu Aotearoa are widely debated.

Oral traditions, iwi Māori and ‘Aotearoa’

It is impossible to briefly summarise the different kōrero held by iwi and hapū concerning the names given to places. A place, like a person or an object, can have multiple names. Kāi Tahu leader Edward Ellison confirmed recently that Aotearoa was not used in the south; the island was primarily known as Te Waipounamu. He suggested that ‘Aotearoa me Te Wai Pounamu’ was the commonly used term for the two main islands.

Rawiri Taonui is an expert in the histories relating to the name Aotearoa and the early voyager Kupe. His investigations into iwi traditions and whakapapa have shed light on the vast array of kōrero relating to this name. Te Ika a Māui (the fish of Māui) is a common name for the North Island, which Maui is said to have fished up from his waka.

Ngāi Tahu leader: Let’s not rush name change – RNZ

Rawiri Taonui, ‘Nga tatai-whakapapa: dynamics in Maori oral tradition’, PhD Thesis, 2005

Written traditions of 'Aotearoa'

In the 19th century, the names ‘Aotearoa’ and ‘Aotearoa me Te Waipounamu’ was used in both te reo Māori and English-language newspapers.

In 1879, in an untitled piece in the Auckland Weekly News, it was asserted that:

the original, genuine name for New Zealand, known to all the Maoris, and which could not be excelled for sweetness, is ‘Aotearoa’. The last syllable simply means ‘large,’ so that, if we are to change the name of New Zealand, and certainly there are good reasons for the change, would it not be best to simply go back to ‘Aotea’? Great inconvenience has been caused by stupid attempts to change well-known native names, sometimes happily in vain.

Governor George Grey used ‘Aotearoa’ in his 1855 Polynesian mythology, and ancient traditional history of the New Zealand race, and in his 1857 book on Māori proverbs, Ko ngā whakapapa me nga whakaahuareka a nga tīpuna o Aotea-roa. William Pember Reeves’ 1898 history of New Zealand was entitled The long white cloud ao tea roa.

The Māori Legal Corpus (a digitised collection of legal and law-related texts in the Māori language from 1829 to 2009) mentions Aotearoa 2,748 times, with one of the earliest written references being Wiremu Tamehana’s October 1862 invitation to chiefs to a hui to discuss the Kīngitanga movement.

Reserve Bank of New Zealand

In 1863, the Forest Rangers (a colonial force established during the Waikato War) captured a flag ‘of red silk with “Aotearoa” written in white cloth across it’ made by Heni te Kiri-Karamau Koka’ of Wairoa. It was displayed in the foyer of Auckland Public Library until it was given to Auckland War Memorial Museum in 1975.

When Pākehā historian James Cowan wrote New Zealand, or Ao-tea-roa (the long bright world) in 1907, he claimed that ‘Māori travellers historically used the word to refer to the entire homeland’. Māori scholar, Henry M. Stowell (Hāre Hongi), contested Cowan’s theories, claiming that Aotearoa was a more ancient name applied exclusively to the North Island.

George Grey – Dictionary of New Zealand Biography

William Pember Reeves – Dictionary of New Zealand Biography

'Māori rebel flag': Aotearoa – Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

James Cowan – Dictionary of New Zealand Biography

Naming 'New Zealand'

Resource: names with no explanation

No place in the world ever received a name which could not be accounted for, though there are hundreds of such names of which we can now give no explanation.

Frederic Farrar (1831–1903), religious cleric, schoolteacher and writer

Think about the quote above. What does it mean to you?

The historical context of the name ‘New Zealand’ begins with Abel Tasman. When he sighted the land in 1642, he named it Staten Landt, believing it might be linked to a Staten Landt close to Cape Horn (at the bottom of South America). This was disproved the following year, and subsequently Joan Blaeu, official cartographer to the Dutch East India Company, conferred the name Nieuw Zeeland (Nova Zeelandia in Latin). Zeeland was one of the two maritime provinces of the Netherlands; Australia was already known to the Dutch as New Holland. ‘Nieuw Zeeland’ stuck.

In 2019 the government's chief historian, Neill Atkinson, discussed the naming of Nova Zeelandia, explaining that it was later anglicised to ‘New Zealand’ by James Cook. In 1835 and 1840, the names ‘New Zealand’ and its transliteration ‘Nu Tirene’ (the spelling varied) were used in the Declaration of Independence and the Treaty of Waitangi. ‘We think about these two traditions of Māori culture and traditions and then the British, mainly English and Scottish element, what's interesting is New Zealand's name actually comes from a different source, it's a Dutch name.’

In 2022 a 70,000-strong petition to officially change the name of this country from New Zealand to Aotearoa was delivered by Te Pāti Māori to Parliament. Below are a series of perspectives around the idea of a changing this country’s name.

Resource: Changing our country's name – iwi Māori perspectives

This teaching activity uses quotes from iwi Māori to help students explore the debate about what name to call this country.

Changing the name of our country – iwi Māori perspectives (PDF, 125KB)

Resource: New Zealand or Aotearoa – political perspectives

Teachers can use quotes from members of various political parties about changing the name of the country from New Zealand to Aotearoa to stimulate class discussion.

New Zealand or Aotearoa – political perspectives (PDF, 189KB)

Resource: Professor Margaret Mutu on citizenship, identity and belonging

This quote from Professor Margaret Mutu (Professor of Māori Studies, University of Auckland) can get students thinking about questions of citizenship, identity and belonging in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Professor Margaret Mutu on citizenship, identity and belonging in Aotearoa New Zealand (PDF, 155KB)

Whakapapa, continuity, and change

Resource: changing New Zealand's name a persistent idea

...if we are to change the name of New Zealand, and certainly there are good reasons for the change...

Unknown author, New Zealand Herald, 1 February 1879

The above quote from 1879 shows how persistent the idea of changing this country’s name has been. Use it to reflect on the following questions:

- What good reasons are there to change the country’s name?

- What good reasons can you come up with to oppose the idea?

The whakapapa of thought is a way in which to explore threads of continuity and change. Powerful and influential ideas can be traced through time as ideologies form and transform. Consider, for example, how New Zealand’s suffragists were inspired both by the equal-rights arguments of philosopher John Stuart Mill and British feminists and by the missionary efforts of the American-based Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU). While New Zealand may have been the first country to grant women the vote, the idea did not originate here. Also consider the rise of Nazism. It was not, sadly, an aberration. It was a grotesque and horrific expression of an ideology with roots in the slave trade.

Change and continuity: Analysis – Te Akomanga

Mana motuhake: Māori resistance to colonisation – Te Akomanga

Resource: Sacred time + Sacred place = History

Whakapapa and the stories attached to them are tapu activities and 'mua' is a sacred place, just as today the activities on the front (mua) of the marae are defined as tapu and those at the back (muri) are not. Sacred place ('wāhi tapu') and sacred time ('wā tapu') might be orthographically represented thus: Wā|hi tapu [i.e., Sacred time + Sacred place = History]. Te reo Māori me ōna tikanga and te ao Māori are resplendent with beautiful, generative metaphors and analogies, which can be accessed and drawn upon if the teacher-student chooses to (a) work hard (b) work hard (c) work hard (d) move with humility (e) operationalise fortitude, courage, resilience, endurance and determination.

Arini Loader (Ngāti Raukawa, Ngāti Whakaue, Te Whānau-a-Apanui)

Look at the quote above, and think the following questions:

- How does thinking about history teaching as a sacred act challenge and inspire you as a kaiako?

- Which wāhi tapu sites near your school can students learn about?

Most people’s lives in these South Pacific islands are underpinned by ideas imported from the other side of the planet. Think of the history of time, private property, capital investment, individualism – the list goes on. These ideas were brought here neatly wrapped up inside a foreign language. Think of the impact these ideas had during colonisation – the understandings and misunderstandings, the tragedies and brutalities, the synergies, the syntheses, and the idiosyncrasies – from the iron patu to the Pākehā Māori. And the impacts are ongoing. There is irrefutable proof that many of today’s dominant ideas are proving deadly for the planet. Yet as Tyson Yunkaporta reminds us, there are indigenous ideas and high-context ways of thinking that might, in concert with sustainable modes of behaviour, stave off ecological collapse and mass extinction.

Patu pora (iron hand weapon) – Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

Tyson Yunkaporta, Sand talk: How indigenous thinking can save the world (2019)

Conclusion

Meet you on Cuba Street.

Let’s take the bus up Queen Street.

Names are ubiquitous and help us navigate the landscape. As such they often get overlooked. Bringing the history of place names and naming conventions into the classroom allows us to access stories from the past, and they can provide an ideal context in which to critically examine ideas such as whakapapa, power, and identity.

Get the name right – Whakaata Māori

Ricky Prebble, Educator-Historian

Community contributions