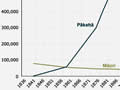

In the period between the first European landings and the First World War, Aotearoa New Zealand was transformed from an exclusively Māori world into a world in which Pākehā dominated numerically, politically, socially and economically. This broad survey of New Zealand’s ‘long 19th century’ [1] begins with the arrival of James Cook in 1769 and concludes in 1914, when many New Zealand men answered the call to fight for ‘King and Country’.

First contacts

By the time the first Europeans arrived, Māori had long settled the land, every corner of which came within the interest and influence of a tribal (iwi) or sub-tribal (hapū) grouping. Abel Tasman was the first of the European explorers known to have reached New Zealand, in December 1642. His time here was brief. His only encounter with Māori ended badly, with four of his crew killed and Māori fired upon in retaliation. Tasman named the place we now call Golden Bay ‘Moordenaers’ (Murderers’) Bay. After he left these shores in early January 1643, Tasman’s New Zealand became a ragged line on the world map. The Māori response to this visit is less well-known, with the exception of fragments of oral tradition that were recorded in the 19th century.

It would be 127 years before the next recorded encounter between European and Māori. The British explorer James Cook arrived in Te Tairāwhiti (Poverty Bay) in October 1769. His voyage to the South Pacific was primarily a scientific expedition, but the British were not averse to expanding trade and empire when opportunities arose. The French were not far behind. As Cook’s ship rounded the top of the North Island in December 1769, a vessel commanded by French explorer Jean François Marie de Surville was only 40 km to the south-west. New Zealand’s isolation from the wider world was at an end.

Over the next 60 years contact grew. The overwhelming majority of encounters between European and Māori passed without incident, but when things did turn violent much was made of the killing of Europeans. The attack on the sailing ship Boyd in December 1809 was one such example. The incident saw some sailors refer to New Zealand as the ‘Cannibal Isles’, and people were warned to steer clear of the country. Little mention was made of the revenge for the Boyd exacted by European whalers, with considerable loss of Māori life. The Anglican Church Missionary Society (CMS) put off its plans to establish the first Christian mission in New Zealand for nearly a decade following these events.

Contact with sealers and whalers – who began arriving in hundreds in the closing decades of the 18th century – and with traders looking to develop new markets, was largely confined to the Far North and the ‘Deep South’. Māori living in the interior had little or no contact with Europeans before 1840.

Those hapū and iwi who did encounter Europeans were often willing and able participants in the trade that quickly developed. Various intermediaries (kaiwhakarite) – people from one culture who lived with the other – were important in helping establish and maintain trade networks as well as bridging the cultural gap. Māori women were often used to keep Pākehā men in the community. Māori also worked as crew members on ships operating between Port Jackson (Sydney) and the Bay of Islands. Much inter-racial contact was ‘strained through Sydney first’. Māori were receptive to many of the new ideas that came with contact. Literacy, introduced by the Christian missionaries, became an increasingly important element of Māori culture from the 1830s.

Musket Wars

Up to one-fifth of the Māori population was killed during the intertribal Musket Wars of the 1810s, 1820s and 1830s. Despite the label, these conflicts were not caused solely by the introduction of European technology in the form of the musket. These wars were about tikanga (custom) and often involved the settling of old scores. They would have occurred whether contact had been made or not.

Māori used the musket in war according to Māori criteria; firearms contributed to, rather than determined, Māori history.

Māori society was organised around and maintained by a number of core beliefs and practices, including mana (status), tapu (controls on behaviour) and utu (reciprocity, the maintenance of societal balance). These core beliefs and practices determined how Māori interacted with other people and what they expected from the Europeans they encountered.

British first steps

In the early 1830s, the Christian missionaries who had now been working in New Zealand for nearly 20 years believed that God’s work was being hindered by a general sense of chaos and violence. They pressured Britain’s Colonial Office to take action, but colonisation was an expensive business and London was not convinced of its necessity. New Zealand was not a sovereign state with a centralised government, so making formal arrangements with Māori was difficult.

Britain’s first steps were tentative. In 1833 James Busby was appointed as Britain’s first official Resident in New Zealand. Given little official support and provided with no means of enforcing his theoretical authority over British subjects, Busby was to seek any assistance he might need from the Governor of New South Wales (who was also reluctant to spend money or time on New Zealand).

Busby attempted to create a sense of identity and collective government by encouraging northern chiefs to choose a flag to represent New Zealand (1834) and sign a Declaration of Independence of New Zealand (1835). The 34 chiefs who initially signed the declaration called upon King William IV of the United Kingdom to become their ‘father and protector’.

The ambitious settlement plans of the New Zealand Company upped the ante. The company’s plans to buy large quantities of land cheaply for resale to British settlers led to concerns among missionaries and British officials that Māori would be defrauded. The Tory sailed for New Zealand in May 1839 with an advance party who were to purchase land and lay out settlements for the emigrants the company was recruiting.

The Colonial Office responded to this challenge by sending Captain William Hobson to New Zealand with instructions to obtain sovereignty over all or part of the country with the consent of chiefs. Once he had done so, New Zealand would come under the jurisdiction of the Governor of New South Wales. Hobson left Britain for New Zealand at the end of August 1839. The first shipload of company emigrants ldeparted soon afterwards, though no word had yet been received as to the success of the Tory’s mission.

Hobson arrived in the Bay of Islands from Sydney on 29 January 1840, a week after the Aurora arrived in Wellington Harbour with the first shipload of New Zealand Company settlers. Neither party was aware of the other – but clearly time was of the essence if they were to achieve their contradictory goals.

Meanwhile William Wakefield, the New Zealand Company’s principal agent in New Zealand, had moved to secure the Company’s position in the Cook Strait region by making major land purchases on both sides of the strait.

Treaty of Waitangi

Within a few days of his arrival in the Bay of Islands, Hobson – helped by British residents including Busby and the missionaries Henry and Edward Williams – drafted the Treaty of Waitangi, which was presented to a gathering of Māori on the grounds of Busby’s home at Waitangi. The merits of the document were debated for a day and a night before more than 40 chiefs, led by Hōne Heke Pōkai of Ngāpuhi, signed it on 6 February. By September, another 500 prominent Māori had signed copies of the treaty that had been sent around the country. For a few months New Zealand became part of New South Wales. From the end of 1840 it was a colony in its own right, with Hobson as governor.

Regarded as New Zealand’s founding document, the Treaty of Waitangi has been a source of debate and controversy ever since 1840. Differences in meaning between the English- and Māori-language versions of the Treaty are at the heart of this debate. While the British maintained that Māori had ceded sovereignty via the treaty, Māori heavily outnumbered the new settlers and at first little changed on the ground.

This is illustrated by the official response to the 1843 Wairau Incident (or Massacre, as it was known to Europeans), in which 22 settlers were killed by Ngāti Toa in a dispute over land. Governor Robert FitzRoy insisted that Ngāti Toa had been provoked by the settlers and took no action against them. The disgruntled settler community took this as confirmation that their needs were seen as secondary to those of Māori.

In 1846 a New Zealand Constitution Act (UK) proposed a form of representative government for the now-13,000 colonists. The new governor, George Grey, argued that the settler population could not be trusted to pass laws that would protect the interests of the Māori majority and persuaded his political superiors to postpone its introduction for five years. Once more settlers felt that their needs were being overlooked. The Colonial Office was bombarded with memorials and petitions, to no avail.

New Zealand's Provinces 1853-1876 (Te Ara)

The new constitution enacted in 1852 established a system of representative government for New Zealand. Six (eventually 10) provinces were created, with elected superintendents and councils. At the national level, a General Assembly was established consisting of a Legislative Council appointed by the Crown and a House of Representatives elected every five years by men over the age of 21 who owned, leased or rented property of a certain value. As Māori possessed their land communally, almost all were excluded (four Māori parliamentary seats were eventually created in 1867, but in a Parliament with 76 members their impact was negligible). New Zealand’s first Parliament met in Auckland in 1854 (it would shift to Wellington in 1865). The governor retained responsibility for defence and Māori affairs until 1864.

The New Zealand Wars

The first major post-treaty challenge to the Crown came in 1845, when Hōne Heke’s repeated attacks on the British flag at Kororāreka sparked the Northern War. Heke believed that Māori had lost their status and their country to the British despite the assurances embodied in the Treaty of Waitangi. The Northern War marked the beginning of the wider North Island conflicts which are collectively known as the New Zealand Wars.

Key campaigns

Northern War (1845–6)

Wellington/Whanganui (1846–7)

Taranaki (1860–1, 1863)

Waikato/Bay of Plenty (1863–4)

Pai Mārire (1864–8)

Tītokowaru’s War (1868–9)

Te Kooti’s War (1868–72)

From the mid-1840s to the early 1870s, British and (increasingly) colonial troops fought to ‘open up’ the North Island for settlement. Contested understandings of sovereignty were inflamed by decreasing Māori willingness to sell land and increasing pressure for land for settlement as the European population grew rapidly.

Around 3000 people were killed during these wars – the majority of them Māori. While many died defending their land, others allied themselves with the colonists, often to achieve tribal goals at the expense of other iwi.

During the Northern War Governor FitzRoy was replaced by George Grey, who secured more manpower and resources before claiming victory at Ruapekapeka in January 1846. Grey, one of the New Zealand’s dominant 19th-century figures, made peace with Heke and his principal ally Kawiti before moving to secure Wellington and Whanganui from allies of the Ngāti Toa chief Te Rauparaha.

The Kīngitanga

In the uneasy peace that followed, an ever-growing settler population continued to covet Māori land. This pressure intensified after 1856, when the New Zealand Parliament achieved responsible government. Most members of Parliament believed their first responsibility was to the settlers who had elected them. And the Colonial Office expected New Zealand to pay its own way – including by acquiring Māori land for settlement.

In the South Island, where few Māori lived, settlers and sheep had spread with ease. But in 1860, 80% of the North Island remained in Māori ownership and most colonists were bottled up in coastal settlements. The fact that some Māori had become commercial farmers supplying the new settlers compounded the latter’s frustrations – especially as, in their eyes, much Māori-owned land was ‘waste land’ (unoccupied).

To counter increasing pressure to sell, some Māori suggested placing their land under the protection of a single figure – a Māori king. Te Wherowhero of Waikato (who had not signed the Treaty of Waitangi) was selected as the first Māori King in 1858. The Kīngitanga (‘King Movement’) attempted to unite all tribes under its banner, but many chiefs refused to place their mana under that of another. Unlike the colonial government and most settlers, the Kīngitanga did not see itself as in opposition to the Queen.

War in Taranaki and Waikato

War erupted in Taranaki in 1860 following Governor Thomas Gore Browne’s decision to accept an offer to buy land from a minor Te Āti Awa chief. The validity of this offer was disputed by the more senior Wiremu Kīngi Te Rangitāke. New Plymouth was besieged and British attempts to lure Māori into a decisive battle failed. The involvement of warriors from Waikato raised fears of a wider conflict. After a truce was agreed in 1861, Grey returned for a second term as governor. Hostilities flared up again in Taranaki in 1863 on the eve of Grey’s invasion of Waikato.

In July 1863 the Waikato War began. Over the next seven months British forces pushed their way south towards the Kīngitanga’s agricultural base around Rangiaowhia and Te Awamutu. On the way they outflanked formidable modern pā at Meremere and Pāterangi, and captured an undermanned pā at Rangiriri. In April 1864 Kīngitanga fighters led by Rewi Maniapoto were heavily defeated at Ōrākau in the last battle in Waikato.

Attention now turned to Tauranga and Bay of Plenty, whose iwi had sent reinforcements and supplies to the Kīngitanga. Despite an overwhelming advantage in numbers and firepower, the British suffered a demoralising defeat at Pukehinahina (‘the Gate Pa’). After they got their revenge two months later at nearby Te Ranga, the campaign came to an end.

South Island settlers objected to helping pay for the fighting and wanted the matter resolved. As gold rushes continued in the South Island, some suggested splitting New Zealand into two separate colonies.

Fresh conflict

The fighting took on a new dimension with the emergence of Pai Mārire from 1862. This new religious faith had grown out of the conflict over land in Taranaki. For most Europeans the movement became synonymous with violence against settlers. Further fighting broke out in 1868 involving the prophet warriors Te Kooti and Tītokowaru. These campaigns ranged across the central North Island from coast to coast, stretching the colony’s military resources to near breaking point. Tītokowaru won several stunning victories before in February 1869 – at the height of his success – his army disintegrated overnight. The fighting with Te Kooti ended when he was granted sanctuary by King Tāwhiao in 1872. Tāwhiao himself formally made peace with the Crown in 1881 and returned to Waikato from Te Rohe Pōtae (the King Country).

Raupatu

After the wars the struggle for land entered a new phase of land confiscations (‘raupatu’).

The Native Land Court

One of the key elements of the 1865 Native Lands Act, the Native Land Court achieved what had not been accomplished on the battlefield: the acquisition of enough land to satisfy settler appetites. Old rivalries between whānau and hapū were played out in court, with Pākehā the ultimate beneficiaries.

The effects varied from region to region. The consequences were most severe for Waikato–Tainui tribes, Taranaki tribes, Ngāi Te Rangi in Tauranga, and Ngāti Awa, Whakatōhea and Tūhoe in the eastern Bay of Plenty. Military settlers were placed on confiscated land to act as a buffer between Māori and European communities. Even Māori regarded as ‘loyal’ found themselves affected by confiscation and the imposition of British notions of property ownership.

From 1879 the south Taranaki settlement of Parihaka became the centre of opposition to confiscation. Its leaders, Te Whiti-o-Rongomai and Tohu Kākahi, encouraged their followers to uproot survey pegs and plough up roads and fences erected on land they considered theirs. Ongoing peaceful resistance resulted in many arrests before the government invaded Parihaka in November 1881. An armed force occupied the undefended settlement and Te Whiti and Tohu were imprisoned and exiled to the South Island for more than a year.

Economic expansion

As war stalled progress in the North Island, the South Island became the mainstay of the colonial economy. Wool made Canterbury the country’s wealthiest province, and the discovery of gold in Central Otago in 1861 helped Dunedin become New Zealand’s largest town. The thousands of young men who rushed to the colony hoping to make their fortune followed the gold from Otago to the West Coast and later to Thames in the North Island. Few struck it rich, but the collective value of the gold that was discovered stimulated the economy.

These developments attracted a young, mobile and male-dominated population. Both provincial and central governments believed that long-term growth and progress depended on the order and stability offered by family life. Various schemes were developed to attract female migrants and families to New Zealand in a bid to help the young society mature.

The Vogel era

Like many frontier societies, New Zealand was vulnerable to the vagaries of a resource-based economy. In the late 1860s gold production fell and wool prices declined. In 1870, Colonial Treasurer (the equivalent of Minister of Finance) Julius Vogel responded by proposing an ambitious development programme whereby large sums would be borrowed from British bankers to help British migrants settle here and speed up the purchase of Māori land. There would be big investments in ‘public works’ – infrastructure essential for economic development, such as railways, roads, bridges, port facilities and telegraph lines.

The centrepiece of Vogel’s plan was a bold promise to build 1000 miles (1600 km) of railway lines in just nine years. In the event, the 74 km of rail lines in 1870 had by 1880 expanded to 2000 km, opening up new regions to Pākehā settlement. British migrants flooded in, almost doubling the colony’s population in 10 years. The Vogel era also spelt the end for the provincial governments which had largely dominated political affairs since the 1850s. New technologies such as railways had begun to chip away at the ‘tyranny of distance’ which had in part justified the formation of the provinces. Their abolition in 1876 marked a recognition that if New Zealand was to progress as a single nation, there could be no place for parochialism.

The post-war decade was also an era of educational progress. A network of Native Schools was created to replace mission schooling of Māori. the universities of Otago and New Zealand came into being, and the Education Act 1877 set the ground rules for a colony-wide public school system.

Vogel is now seen as a nation-building visionary, but he was a controversial figure in his time. When the colony slipped into a long economic depression in 1879, many blamed his over-ambitious borrowing programme. Prices for farm produce fell and the market for land dried up. Unemployment grew in urban areas. Women and child workers were exploited, and evidence emerged of sweated labour and poor working conditions in a number of industries. Questions were asked about how New Zealand should support its poor. There was no state welfare system and localised forms of charitable aid had proven to be inadequate when put under pressure.

The hard times faced by many families led to renewed debate about the place of alcohol in New Zealand life. Liquor, it was argued, caused many men to neglect their responsibilities to their families. The temperance and prohibition movement gathered momentum and contributed to the emergence of a campaign for women’s suffrage. With women and children bearing the brunt of alcohol abuse, enfranchising women was seen as crucial to any real change. After a hard-fought and at times bitter debate, New Zealand women became the first in the world to gain the right to vote in national elections in 1893.

The first successful shipment of frozen meat to England in 1882 offered hope, and the new technology would eventually cement New Zealand’s place as ‘Britain's farmyard’. The ability to export large quantities of frozen meat, butter and cheese restored confidence in an economy based on agriculture and speeded up the transformation of the landscape from forest to farmland.

The Liberals

The 1890 election saw the end of the long-standing practice of ‘plural voting’, whereby men could vote in every electorate in which they owned property. One of the most significant in New Zealand history, it took place against the backdrop of the country’s first big nationwide strikes after workers at ports around the country walked off the job in support of Australian trade unionists. The maritime strike caused enormous disruption to the colony’s trade and transport networks. Though class consciousness grew among some workers, the strike ended after almost three months in total defeat for the seamen and the unions allied with them.

The outcome of the 1890 election became clear when Parliament met in early 1891. Recognised as New Zealand’s first political party, the victorious Liberals were led initially by John Ballance and following his death in 1893 by the larger–than-life Richard John Seddon. ‘King Dick’ dominated the New Zealand political landscape for 13 years and the Liberals remained in power until 1912. Their economic and social reforms – and their egalitarian rhetoric – continued to shape the political agenda well into the 20th century.

The Liberals won support from urban wage-earners as well as those living in provincial towns and small farmers. As an export-led economic recovery took hold, the Liberals emphasised farming for export rather than as a means of supplementing the incomes of wage-earners living on smallholdings. Liberal land policy aimed to achieve closer settlement by small farmers by ‘bursting up’ (subdividing) the ‘big estates’, most of which were in the South Island.

The Liberals’ vision for ‘God's own country' saw yet more Māori land acquired for settlement. Minister of Lands John McKenzie shared the common Pākehā view that much Māori land was not used for ‘productive’ purposes and was therefore ‘wasted’. When Europeans obtained land, they immediately turned it ‘to good account’. Such attitudes and policies contributed to the fact that Māori now held less than 15% of the land that had been in their possession in 1840.

Other laws designed to improve life for ‘ordinary New Zealanders’ were also introduced. The industrial arbitration system, old-age pensions, and restrictions on working hours for women and young workers led some overseas observers to view New Zealand as a ‘social laboratory’ and a ‘working man’s paradise’.

Emerging identity

From 1886 on, the majority of non-Māori people living in New Zealand had been born here. The term ‘New Zealander’ had originally referred to Māori, but now took on a new meaning. However, New Zealand’s identity remained largely contained within an imperial identity. The close economic ties with Britain reinforced the loyalty of New Zealanders to an empire that secured their place in the world. Most Pākehā continued to see themselves as British and referred to Britain as ‘home’.

This loyalty could be seen in New Zealand’s enthusiastic support for Britain when the Second Anglo-Boer War broke out in South Africa in 1899. This was the first time New Zealand troops served overseas. Seddon proudly confirmed that the ‘crimson tie’ of empire bound New Zealand to the ‘Mother-country’.

When the Commonwealth of Australia was established in 1901, New Zealand declined to become its sixth state. Federation with Australia was rejected for a number of reasons, not least because we too aspired to ‘identity, status and a grander future’. Some feared federation might put New Zealand’s social reforms at risk, while others believed we represented a better ‘type of Britisher’, given the ‘convict stain’ of Australia’s origins.

Federation ultimately consolidated national identity on both sides of the Tasman and strengthened the view that New Zealand should not give up its growing independence. Symbols of nationhood emerged, including a new flag (1902) and a Coat of Arms (1911)

In 1907 New Zealand became a dominion within the British Empire. Some trumpeted what they saw as a ‘move up’ in the ‘school of British nations’, but in reality little changed. New Zealand was no more and no less independent from Britain than it had been as a self-governing colony.

The Reform era

Premier Richard Seddon’s five consecutive election victories have never been matched. Though he tipped the scales at 130 kg, his death at the age of 60 while returning from Australia in 1906 came as a shock to New Zealanders.

Seddon was a hard act to follow. Joseph Ward, his deputy since 1899, led the Liberals to an easy victory in the 1908 election but lacked Seddon’s man-of-the-people appeal to workers. Ward was criticised for being verbose and for being too interested in his own appearance and public profile. The election of December 1911 made it clear that voters had finally grown tired of the Liberals; William Massey’s right-wing Reform Party won four more seats. The Liberals clung to power with the support of independent MPs. Ward stepped aside as leader in March 1912, but his successor Thomas Mackenzie was unable to stem the outgoing tide. On 6 July 1912, several defections in the House gave Massey the numbers to form a government.

‘Farmer Bill’ Massey

The Reform Party was supported by the many farmers who had become frustrated with the Liberals’ policy of leasing rather than selling Crown land. They were encouraged by Reform’s promise to make it possible for them to own the land they had developed. But despite his nickname, ‘Farmer Bill’ Massey also gained the support of many workers in the rapidly growing North Island towns and cities. These people wanted to ‘get ahead’ through home-ownership, white-collar employment and secondary/technical education.

While Massey was a farmer, several members of his cabinet were urban businessmen or professionals. The Liberals had been criticised for manipulating the public service by dispensing patronage. To end ‘political cronyism’ and ‘jobs for the boys’, the Reform government established an independent Public Service Commissioner responsible for the appointment and promotion of public servants.

Perhaps what cemented the perception of the Reform Party as a ‘farmer’s party’ was its response to two of the most bitter industrial disputes in New Zealand's history: the 1912 Waihī miners' strike and the 1913 waterfront and general strikes. With the country split into two irreconcilable camps, the government sided firmly with employers in opposing industrial militancy.

At the climax of a bitter six-month strike in the gold-mining company town of Waihī, one of the striking workers, Fred Evans, was mortally injured in a clash with police and strike-breakers. Violent clashes between unionised workers and non-union labour erupted once again during the 1913 waterfront strike, after industrial action on the wharves disrupted the ability of farmers to get their products to overseas markets.

The Massey administration, in which Attorney-General Alexander Herdman played a key role directing Police Commissioner John Cullen, enlisted thousands of ‘special’ police, many of them farmers on horseback, to break the strike and crush militant labour. The two-month struggle involved up to 16,000 unionists across New Zealand and saw violent clashes between strikers and mounted special constables known as ‘Massey’s Cossacks’. The strike ended in December 1913 with the defeat of the United Federation of Labour.

Such actions earned Massey the ‘undying hatred of many urban workers, an enmity passed on to their children’. Conservative voters – farmers, in particular – saw Massey’s stand as firm and decisive; he had met the fiery rhetoric and ‘intimidatory tactics’ of the ‘Red Feds’ head-on and won.

New Zealand goes to war

In 1909, Prime Minister Ward announced that New Zealand would fund the construction of a battlecruiser for the Royal Navy. This gesture was a response to a perceived German threat to Britain and reflected awareness that a strong British Empire was critical to New Zealand’s security. HMS New Zealand cost New Zealand taxpayers £1.7 million (equivalent to $350 million in 2023). When the ship visited the dominion in 1913 for 10 weeks during a voyage around the world, an estimated 500,000 New Zealanders – half the population - inspected their gift to Mother England.

The Defence Act 1909 introduced compulsory military training, with all boys aged between 12 and 14 required to complete 52 hours of physical training each year as Junior Cadets. Developing fit and healthy citizens was seen as vital to the strength of the country and the empire. The Boy Scout movement had arrived in New Zealand in 1908 with similar aims of producing patriots capable of defending the empire. Boys were taught moral values, patriotism, discipline and outdoor skills through games and activities. In the classroom, the ‘three Rs’ were backed up by instruction in moral virtues and imperialistic ideals.

On 5 August 1914, word reached Wellington that the British Empire was at war with Germany. As they had done when the South African War began, New Zealand men reacted enthusiastically to the empire’s call to arms. Germany’s invasion of Belgium, another small country, struck a chord with many. Thousands soon signed up for service, desperate not to miss out on an event many expected to be over by Christmas. The First World War would ultimately claim the lives of 18,500 New Zealanders, with another 41,000 wounded. The extent to which it forged a sense of national identity has long been debated. What is certain is that previously little-known places thousands of miles from home with exotic-sounding names such as Gallipoli, the Somme and Passchendaele were forever etched in the national memory.

The First World War would have a seismic impact on New Zealand, reshaping the country’s perception of itself and its place in the world. The war took 100,000 New Zealanders overseas, most for the first time. Some anticipated a great adventure but found the reality very different. Being so far from home made these New Zealanders very aware of who they were and where they were from. They were also able to compare themselves with men from other nations, in battle and behind the lines. Out of these experiences came a sense of a separate identity.

[1] In 1962 the English historian Eric Hobsbawm outlined the case for what he described as ‘the long 19th century’. As a Marxist, Hobsbawm’s analysis was book-ended by the French Revolution of 1789 and the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. The American historian Peter Stearns adopted a similar approach but started in 1750 and concluded with the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. These approaches recognise that historical forces and processes cannot be shoehorned into conventional periods of time such as decades and centuries. In this survey we have taken a similar approach in examining the powerful historical processes which transformed New Zealand from an exclusively Māori world into one dominated by Pākehā.

Further information

This web feature was written by Steve Watters and produced by the NZHistory.net.nz team.

Links

- Brief history of New Zealand (Te Ara)

- NZHistory topics on: Pre-1840 history; Treaty of Waitangi; New Zealand's internal wars; The Vogel era; South African War

Books

- James Belich, Making peoples, Penguin, Auckland, 1996

- James Belich, Paradise reforged, Penguin, Auckland, 2001

- Bronwyn Dalley and Gavin McLean (eds), Frontier of dreams, Hodder Moa Beckett, Auckland, 2005

- Michael King, Penguin history of New Zealand, Penguin, Auckland, 2003

- Anne Salmond, Between worlds: early exchanges between Maori and Europeans 1773–1815, Viking, Auckland, 1997